The Naval War of the Pacific. 1879-1884 Saltpeter War. No. 3111

Thanks to Casemate Publishing & IPMSUSA for the review copy!

Piotr Olender is a Polish naval historian who lives in Gdansk, Poland. He has authored a series of books via MMP Books and Casemate that delve into the little-known, predominantly naval wars around the world in the last half of the 1800s and early 1900s.

This particular offering gives an operational history of the so-called Saltpeter War, or The War of the Pacific, that ultimately defined the geographic borders of three western countries of South American – Bolivia, Chile and Peru. This book is one of the Maritime Series published by Stratus s.j. in Sandomierz, Poland.

What You Get

A 11.8 X 8.2 inch paperback book 3/8 inches thick. Lavishly illustrated, although after the front cover, everything is B&W – two Tables, 20 maps, 69 prints/paintings and 115 photos. The major humans and ships involved in the war were pictured, as were many battle sites, usually immediately post-battle. The text is well-written (although there were a few minor typos such as is/are substitutions and missing letters in words that a spell checker would let go). I would have liked better explanations of antiquated words such as mitrailleusse and fougasse (multi-barreled rifles and flaming land mines), but this did cause me to look up and learn new words. The writing style is obviously from a non-English language native, but is clear and understandable. Because of the many illustrations and photos in the book, this is a relatively quick read for a book this length. Just keep the main map in the introduction tabbed for frequent referencing of where the actions were.

There are 19 sections to this book – the first part being the origins of the conflict and the military capacity of each combatant at the start of the war. Chapter 3-17 are each devoted to a chronological presentation of each discrete operation, battle or short campaign, with a summary Outcome of the War and Appendices.

Like many wars, this one too was all about the money. At the start, Bolivia had a coastal region shared with Chile and Peru that was the Atacama desert – the world’s driest land – a desolate wasteland. All three countries had won independence from Spain earlier in the century by bloody revolutions, and all three countries were wracked by frequent changes in government and wars with neighbors – some bloodless and some definitely not bloodless. Also, all three were financially burdened by huge debts (internally and to foreign banks), and primarily agrarian. Chile was probably the best off of the three but was just finishing up a war with Argentina over the southern tip of South America (Tierra del Fuego). All the countries had relatively small armies (under 10,000) with large reservist reservoirs of untrained citizens. Bolivia had no navy, but both Peru and Chile had recently purchased foreign warships that had been used in previous wars and in preparation for the next. Peru and Bolivia were Allies, mostly of convenience for sharing the coastal region with Chile around the 24th parallel.

When vast riches appeared in the shared area, the inevitable scramble to take control of these natural assets was on, and all knew it would bring yet another war. The new riches were mountains of guano deposits mined for fertilizer and making munitions, and soon thereafter the world’s biggest source of easy-to-mine saltpeter, which supplanted guano for making fertilizer and munitions (gunpowder & explosives). The boom/bust cycles further weakened economies and hastened conflict to retrieve riches. Bolivia was a major exporter of copper, silver and tin, and the shared area was also rich in those and other minerals. The major European powers and the United States were the paying customers, and were always hovering around these countries’ power centers to look after their economic interests and citizens.

Old war grievances and need for revenue to finance huge debts led to posturing over who would get the riches, and it soon escalated to armed interventions which led to declarations of war by Chile against Peru and Bolivia. But unlike most wars, the battlefields were in the world’s worst desert, making ground transport almost nil, but reachable by a few ports strung along the coast – thus setting the stage for a naval struggle to determine the winner.

The importance of this book is the rise of seapower as a strategic war winner, and a testing ground for new technologies that revolutionized naval power. Most of this book describes the naval maneuverings and battles between Chile and Peru (Bolivia was an unwilling participant and actually did not want its coastal share – it shipped most of its exports through Argentina, a shorter trip to the buyers in Europe and USA than going via the Pacific with minimal infrastructure). Few railroads, fewer roads and miserable conditions made logistics king.

At the start, Peru and Chile had small and roughly equivalent navies. Each country had two capital ships each – ironclads of differing types and a handful of frigates, corvettes and gunboats – minor warships. A few old US Civil War monitors and new-fangled torpedo boats (the charge was attached to the boat which had to ram its target) were involved as was early use of self-propelled torpedoes, and new types of mines. Peru had more sophisticated naval facilities, but Chile rapidly caught up since the war was waged on Peruvian soil. The race was on to mobilize and equip armies as rapidly as possible – neither side acquired any substantial naval additions during the conflict. But receiving shipments of foreign munitions was critical for success. Whoever controlled the seas could blockade and strange the other country. Which is exactly what happened.

Peru quickly won early naval battles, delaying the ability of Chile to send their army via ships to the desert area. However, the fickle finger of fate soon caused Peru to lose both of her ironclads. Even worse, their remaining, and modern ironclad, the Huascar, was trapped and captured by Chile, repaired and sent to fight against Peru. The Huascar still floats as a museum ship in Valparaiso, Chile. After that Battle of Angamo, the tide of war swung to Chile’s favor, and led to the inevitable buildup of land forces which slowly and inexorably picked off Peruvian towns until ultimately sacking the capital – Lima. The ground actions were covered rather quickly because by then they were predictable. Yet the war still had a couple more years to go before Peruvian changes in governments were able to legally surrender and enact a peace treaty.

Lessons learned were taken into account by the world powers. What was important was command of the sea which gave freedom of mobility for military forces, and prevented the opponent to build up their military. Trade and commercial warfare was first seen to be a war winner, as Chile intercepted shipments of arms and provisions to Peru as well as preventing exports, and that income. Because of the mobility of the Chilean navy, the numerically superior Peruvian army was spread out and defeated in detail, not knowing where the Chileans would strike next – the entire Peruvian coast was being raided. The effect on public morale was devastating, and helped to make Bolivia exit the war early. Conduct of both armies against the civilian populations was ghastly, and the Peruvians suffered harshly.

This war did set today’s boundaries of these countries, landlocking Bolivia to this day. This was made most navies and their weapons obsolete. Breech-loading, rifled cannons with explosive shells ruled the waves and the coastal lands, initiating an arms race of bigger, more powerful, more armored and faster warships. Torpedoes failed miserably in action, but just their threat paralyzed entire fleets, naval movements, and conduct of the war – something that was accentuated in the next century when the threat became reality.

Summary

I thoroughly enjoyed this book, as a naval historian wannabe. This book was a pleasure to read and had sufficient detail keep you wanting to read it all in one sitting (I did not but wanted to). It had important lessons for everything naval that followed, and for geographical boundaries that shaped what we see today in the area. It also showed how luck, fate, human folly and the fog of war never stop determining outcomes. The triumphs and travails of the Peruvian ironclad Huascar is the main event of this book and the war. But for a few isolated incidents, the Peruvians could have held on to their coastal area by doing exactly what Chile did to them – and our world would be different. Losing their two capital ships in the initial phase – one to self-inflicted grounding, the other to predictable overuse and falling into a trap – sealed the fate of Peru.

Highly recommended for its lessons on how to win, and lose, a war. Also for its almost soap-opera nature of luck and ambition ruling the waves. And for being an obscure bit of history that greatly affected the world we have today.

Figures

- Figure 1: Front cover of The Naval War of the Pacific, 1879-1884, Saltpeter War.

- Figure 2: Back cover of The Naval War of the Pacific, 1879-1884, Saltpeter War.

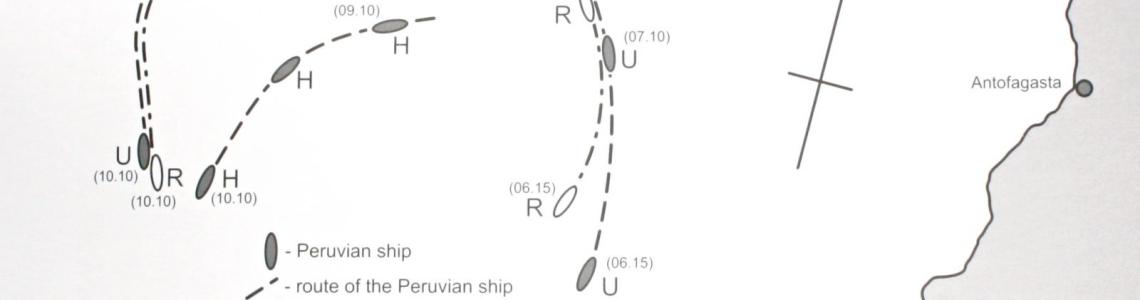

- Figure 3: Map of capture of Chilean transport Rimac by Peruvian warships.

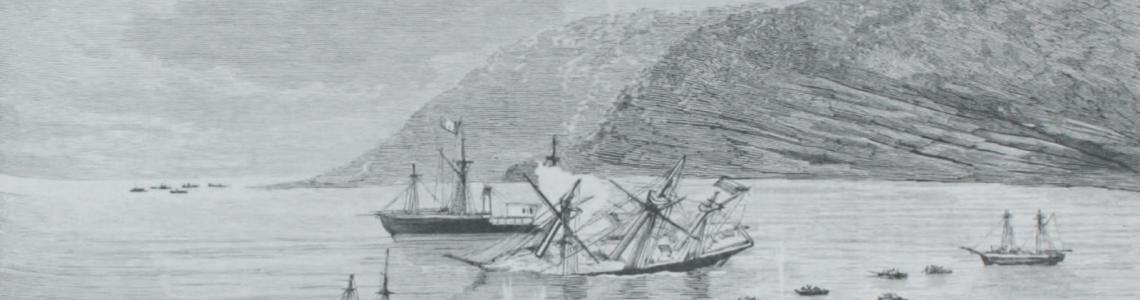

- Figure 4: Battle of Iquique showing sinking of Chilean corvette Esmeralda.

- Figure 5: Battle of Angamos between Peruvian ironclad Huascar and Chilean ironclads.

- Figure 6: Surrender of battered Peruvian ironclad Huascar, end of Peruvian Navy hopes.

- Figure 7: Huascar as Present Day Museum Ship for Both Peru and Chile in Tulcahuano, Chile.

Reviewer Bio

Luke R. Bucci, PhD

Luke built all kinds of models starting in the early '60s, but school, wife Naniece, and work (PhD Clinical Nutritionist) caused the usual absence from building. Picked up modeling to decompress from grad school, joined IPMSUSA in 1994 and focused on solely 1/700 warships (waterline!) and still do. I like to upgrade and kitbash the old kits and semi-accurize them, and even scratchbuild a few. Joined the Reviewer Corps to expand my horizon, especially the books nobody wants to review - have learned a lot that way. Shout out to Salt Lake and Reno IPMSUSA clubs - they're both fine, fun groups and better modelers than I, which is another way to learn. Other hobbies are: yes, dear; playing electric bass and playing with the canine kids.

Comments

Add new comment

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Similar Reviews