The History of Science Fiction and its Toy Figurines

“The History of Science Fiction and Its Toy Figurines” by author Luigi Toiati is a substantial and weighty hardback of 528 glossy pages with 470 pictures (See Photo 1). Although it may feel like one, the author claims in the Forward that it is not an encyclopedia or boring treatise or catalogue, but instead the reader should “consider it a promenade through sci-fi and the toy figurines linked to the subject.” And while the author doesn’t necessarily agree with those science fiction (SF) authorities he cites who trace the origins of the genre back to the ancient times of the Bible, Hinduism, Plato, or Lucian of Samosata (a 2nd-century Syrian satirist and rhetorician), his review of the aforesaid genealogy is extensive and at times tedious.

The book’s back cover states that Luigi Toiati is an Italian who began his career in London, England and who now lives in Rome with his wife Monica, the cofounder of his research agency. He has a degree in sociology and a deep interest in Semiotics (the study of signs).

He was a professional figure painter for 45 years who created his own brand of toy soldiers. As such, he would likely be a star at an annual Miniature Figure Collectors Association (MFCA) meeting.

To me, this publication can be considered two books. While some connection is obvious, particularly with the modern SF era (post 1920s), Part One, “A Short History of Sci-Fi” and Part Two “Sci-Fi Figurines and Other Trifles” can be approached individually. One might also find it to be a good coffee table book, whereas a reader can pick it up and go to any specific chapter of interest and enjoy it (See ToC Photos 2 and 3).

Overall, I found the book at once intriguing and frustrating, yet compelling. If one wants to delve into the extreme depths of the definition of SF, or to try to determine its origins, this book is for you, but be ready for a literary history replete with citations of many other works and obscure references you’ve likely never heard of, so consider it a learning experience. The former forces the reader through the many tangential paths of mythology and religions, with concomitant yet exhaustive explanations.The average SF reader probably doesn’t care if Lucian’s True History (2nd century A.D.), Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), Cyrano de Bergerac’s Empires of the Moon (1657), or Swift’s Gulliver (1726) are considered “proto sci-fi.”

Consider this paragraph in Ch.3:

In the City of the Sun by Tommaso Campanella (1602), allegory and myth intertwine with rationalistic investigation.It is, I assume, the same as Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) and does not describe a fictional island for the mere pleasure of speculating, but with the intent of transmitting deep considerations of political philosophy, which would have later influenced history.Similarly, one can consider Aristophanes as a playwright despite some Greeks denouncing his comedies as slander, but his work is that of a fierce enemy of contemporary philosophers, so I imagine that he wrote his Clouds not to anticipate future space journeys, but to vitriolically lampoon the customs of his time.

Get the picture? If this is your cup of tea, this book has it in spades.

Toiati writes as a literary intellectual, so being a multi-degreed engineer and not a liberal arts major by any means, I needed to keep a dictionary and thesaurus handy to decipher the many uncommon words, idioms and foreign phrases that he employs. Here are a few examples with definitions for your convenience:

- Upanishads ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism

- in nuce in a nutshell

- mirabilia wonders or marvels.

- Procrustean bed a scheme into which something is arbitrarily forced.

- outremer distant lands

- excursus a digression that contains further exposition of some point

- hermeneutics the science of interpretation

- conte philosophique philosophical tale

- fin de siècle. the end of the century

- logorrheic excessive and often incoherent wordiness

- malgre lui despite himself

- mise-en-abyme story within a story

- divulgation making public

- oeuvre complete body of work

- propaedeutic introductory instruction

Although others may not find it so, learning new words and phrases, or encountering those I may have long forgotten, was actually a fun part of reading this book.

One subject discussed in in this book concerns social commentary made by SF authors, and in particular, political satire. While I’ve enjoyed SF over the years, I never at any time viewed it as social or political commentary, whether in books or film. For me, doing so destroys the enjoyment of the escapism that is science fiction. Check out the author’s referencing of Adam Robert’s1 evaluation of the book Body Snatchers (1955) by Jack Finney and the subsequent film Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) by Don Siegel:

The effectiveness of both texts depends to a large extent on how finely balanced they are as political satire. Indeed they can be read both as right-wing McCarthyite scaremongering – Communists from an Alien place are infiltrating our American towns and wiping out their American values, and the worst of it is they look exactly like Americans – and as left-wing liberal satire on the ideological climate of conformism that McCarthyism produced, where the lack of emotion of the pod people corresponds to the ethical blind eyes turned by Americans to the persecutions of their fellows by over-zealous McCarthyites.

I saw the film as a youngster and later as an adult, i.e., both before and after I knew of McCarthyism. In neither case did I consider the work as political satire.It was simply a sci-fi movie where aliens invade, and which had an ominous ending. I gladly dispense with an author’s satirical evaluations, with their right-wing or left-wing viewpoints, and especially the politicalleanings which invariably seem to favor the latter.2

One topic Toiati avoids is discussing the reprehensible conduct of certain SF authors, two in particular that are featured in this book, namely Arthur C. Clark (pedophilia) and one of the more famous female writers he cites in Sec. 3.11, Marion Zimmer Bradley (aiding her husband’s pedophilia and her own child abuse of her daughter). Toiati mentions Bradley’s enthusiasm for Women’s Rights and Gay Rights but avoids the negatives. I won’t get into the details regarding either Clarke or Bradley, leaving that to the reader, but in the name of decency, one may choose to avoid their works once one knows their personal history.

Toiati’s opinion of the era of the birth of SF is actually best described on the first page of Ch.5 in Part 2:

Nor have I ever made a secret . . . that for me, science fiction proper – that is, the combination of fiction and technology and its eventual consequences(reviewer’s italics) – has been around since someone like Verne or Wells began creating it, and since someone else began calling it as such in the first decades of the previous century. That is, since Hugo Gernsbach published the first issue of Amazing Stories in 1926, which gave the character Buck Rogers his baptism of fire in 1929 and worked other similar miracles; or since John W. Campbell started the Golden Age in 1937 with Astounding Science Fiction, up to the threshold of the 1960s.

Therein lies the time period, i.e., the 1920’s, that both I, and my close friends who happen to be avid SF fans and memorabilia collectors, consider to be the birth of the genre. Anything prior is fodder for academic debate by literary historians.Indeed, my buddies and I can’t be too far off, as Toiati confirms in Part 2 of the book, “Sci-Fi Figurines and Other Trifles”:

We were at the dawn of the mass media, which evidently contributed to this benevolent, fantastic pandemic. It follows that the history of science fiction figurines – and toys (which we will not treat) – begins in Space, and chronologically in the first decades of the twentieth century; and that their subjects were above all relevant to the adventures narrated by the mass media of their time, and therefore focused mainly on…Space!

We enter “Space” in what is for me the most interesting parts of this book, i.e., in Chapter 3, the 143-page Short (!) History of Sci-Fi, in particular Sections 3.7 to 3.9, which cover the “Golden Age” of SF, and Ch. 4 where the author delves into the modern, early TV “space operas”.Those chapters contain the authors I am familiar with and the TV shows of the early 1950s that I enjoyed, and whose memories I cherish even today as a member of the Solar Guard3.

In Section 3.7, At Last, Science Fiction, we learn of Hugo Gernsback, whose desire for profit led to the historical first:

On April 5, 1926, Hugo Gernsback - inventor, writer, editor and most of all publisher – added another specialized publication to the newsstand of the nation. The magazine was Amazing Stories, and it was the world’s first science fiction magazine.

Gernsback was a controversial figure, with some critics claiming he was one of the worst disasters ever to hit the science fiction field, his magazines being “ghetto fashion”. But Toiati sums Gernsback’s contribution to SF by citing James Gunn4:

Looking back upon the place, it may have been a ghetto, but it was a golden ghetto, a place of brotherhood and opportunity and wonder. Before Gernsback, there were science fiction stories. After Gernsback, there was a science fiction genre.

Toiati entitles Section 3.8, 1930 – 1940:Stars, Aliens and ESP. Navigating the Golden Age. Unambiguously, he considers the real SF period to begin in the 1920s and enters said “golden age” around 1930. He cites that the pulps built a new style or formula from nothing, called legitimately Sci-Fi. Regarding the aforesaid formula, what is noticeable about Martians, monsters and aliens is that they are used to arouse wonder, terror and excitement, rather than for any allegorical or satirical end.

In this same section, I learned of a number of key authors, e.g., Edmond Hamilton who “invented a galaxy of inhabited worlds organized into a Council of Suns, in turn strengthened by an Interstellar Patrol.”Further:

As any sci-fi aficionado can see, the latter was the embryo of the first radio and television serials about space forces defending the Universe, the first of legions of films in recent years about confederations et similia.

Also presented is Jack Williamson, a most prolific writer who published from the 1920s to the 70s. He wrote hundreds of novels and gained early success via the serial “The Legion of Space” in a 1934 Astounding Magazine.

Toiati attributes the inauguration of the Golden Age of SF (1939) to four authors, whom he calls the four musketeers of sci-fi:A. E. Van Vogt, Theodore Sturgeon, Isaac Azimov5, and Robert Heinlein. Toiati goes into their histories and writings in some detail, which I found quite interesting, as many of the SF stories I read as a teenager were by these authors. It was one of the highlights for me in reading this book.

James Gunn further emphasizes the importance of this era:

The dozen years between 1938 and 1950 were Astounding years. During these years the major science fiction editor began developing the first modern science fiction magazine, the first modern science fiction writers, and, indeed, modern science fiction itself.

Toiati continues this “short” chapter all the way through the 1960s to the present. I only scanned these periods as their content never grabbed me as that of the Golden Age6. I apologize, but Feminist writing, European and Japanese New Wave, dystopian Cyberpunk, Anime, and Crapsack World hold no interest for me, but they’re all presented in this book should the reader care to indulge.

My favorite topics in the book are found in Chapter 4, for therein lies the source of my greatest childhood adventures, the Space Operas. I could not get enough of Tom Corbett: Space Cadet (both the books and the TV show) and Space Patrol, both Saturday morning staples that I lived for from the time I found them in 1953 until their cancellation in 1955. With the help of the Solar Guard cadets whom I meet with regularly, I have acquired almost the complete Space Patrol TV show filmography, which never fails to please when I desire a trip down memory lane. Toiati does not cover either Rocky Jones, Space Ranger or Rod Brown of the Rocket Rangers in this book. I don’t know if that was an oversight or a complete miss, but both have their aficionados.Nevertheless, reading about their genesis and the premiums offered for a cereal box top or lid from a can of Nestles Eveready Cocoa, the story of those programs are a highlight in this book for me.

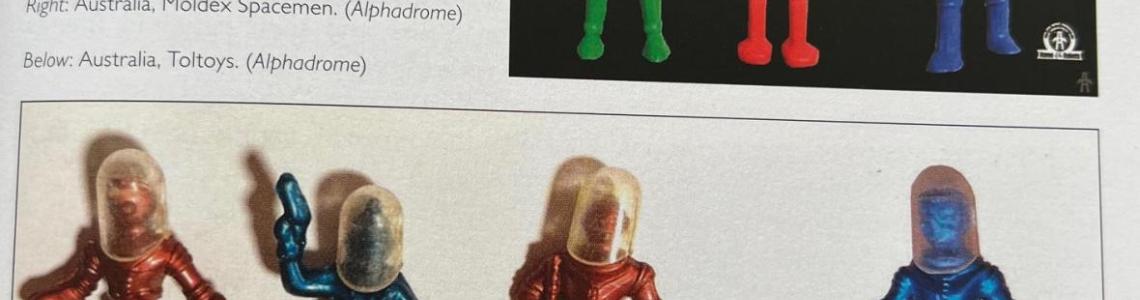

It is in Part 2 of this book that a real “promenade” is found, i.e., through the many pages and photographs of the toy figurines. As aforementioned, the book covers all the way from 1934 Buck Rogers to today’s Transformers. This is where I think the book qualifies as one for the coffee table. Pick your time frame and peruse through any era in over 90 years of figurines, playsets, advertisements and artwork. It should be noted that many figurines depicted are foreign and are not those that a US fancier may know of or have encountered. Toiati shows figurines from just about everywhere in the world, including Italy, Spain, Portugal, England, Germany, Russia, and Australia.

This paragraph best expresses Toiati’s affection for toy figurines and the inspiration he felt in composing this book:

A toy soldier, a figurine, is a sign of love, a tribute to the genius of the imagination, a passport to worlds ruled by the imagination: and watering the plant of one’s imagination is the greatest gift a human being can give oneself. I also believe – from my own experience – that the manufacturer himself, even though his ultimate goal may be primarily commercial, or the figurine he has created may help to convey questionable ideological principles, is also and above all motivated by love in making it. The love of giving a gift to the child (and tomorrow to the collector), by giving him a figurine that will accompany him on wonderful adventures, which he himself, the maker, often experimented as a child.

To use an American idiom, he’s basically “letting it all hang out.’ Imagine if Toiati loved modeling as much as he loves figurines. That would be something to read. I daresay that would be the all-time IPMS best seller.

In Conclusion

“The History of Science Fiction and its Toy Figurines” can thus be summed up as nothing less than a work of love. Taken as such, all the references, citations, idioms, and obscurities, which at first seem overwhelming to the reader, reflect Toiati’s love of the subject. The book is a good reference for those who don’t care for a complete encyclopedia of Sci-Fi, but who wants an excellent reference and exposé of the subject.

Thanks to Casemate Publishers for providing the book and the IPMS Review Corps for permission to provide this review.

Footnotes

- 1 Adam Roberts, Science Fiction (2000) and The History of Science Fiction (2006) is an author frequently cited by Toiati. Others frequently cited include John Clute and Peter Nichols, SFE, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, and Brian Aldiss, Billion Year Spree.

2I’m not a McCarthyite, but I can’t help but notice that the right-wing viewpoint is “scaremongering”, while the left-wing viewpoint is “liberal satire”. It should be noted that there were a lot of Communists in the pre- and post-WWII US government, and there may yet be a few at present. (There were also a number of SF authors who were Communists.)

While McCarthy’s methods were questionable, in America, calling out communists for what they profess vis-a-vis individual liberty and freedom should be welcomed, not spurned.

- 3See www.solarguard.com for info and history of the “Space Operas” Space Patrol, Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, etc.

- 4James E. Gunn, Alternate Worlds:The Illustrated History of Science Fiction, (1975).

- 5Isacc Azimov was the commencement speaker at my bachelor’s degree graduation ceremony. He was by far the most interesting and engaging speaker in any presentation or commencement I’ve ever attended.

- 6Indeed, 1965-68’s Lost In Space is considered by me and my contemporary sci-fi cohorts to be the worst SF program ever foisted on a TV audience.

Comments

Add new comment

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Similar Reviews