We Killed Yamamoto

The planning, execution and consequences of Operation Vengeance – the interception, shoot-down and death of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the architect of Japan’s surprise attack upon the U.S. Fleet at Pearl Harbor – have generated a sizable literature. This Osprey title, the 53rd in its Raid Series, is a succinct but comprehensive summary of that material.

Author Si Sheppard begins with a look at U.S. efforts to read Japanese secure message traffic – codes and cyphers – that began to slowly gather momentum soon after World War I, only to be abruptly halted in 1929 by Henry Stimson, President Hoover’s new Secretary of State, on the grounds that, as Stimson had famously said, “Gentlemen do not read one another’s mail.” Fortunately, an outbreak of realism soon followed, and in the 1930s both the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army made important breakthroughs in intercepting and reading encrypted Japanese military and diplomatic messages. Unfortunately, their efforts were separate and insufficiently shared, both because of the sensitivity of the subject and, to a sad extent, because of inter-service rivalry.

The shock of Pearl Harbor overcame some of that rivalry, at least as to communications intelligence, and Sheppard deftly outlines its critical contributions to the U.S. Navy’s successes in 1942. Checked at Coral Sea and painfully punished at Midway, the Japanese focused their attention upon the Solomon Islands and what soon became the Battle for Guadalcanal. It was a close-run thing. The key was to establish and hold an airfield from which to defend the island and its surrounding sea approaches. U.S. Marines were able to seize an unfinished Japanese airstrip on Guadalcanal in early August. Quickly completed and named Henderson Field, it soon hosted a motley force of USMC F4Fs and Navy SBDs and TBFs, along with a handful of AAF Airacobras. They were joined by two AAF P-38 squadrons in November. Further Japanese efforts to reinforce and supply its island forces were effectively thwarted, and by year’s end the tide had fully turned. Japan began to quietly withdraw the starving remnants of its forces from the island; the last elements departed in early February 1943.

Even as the Japanese presence faded away, the U.S. moved to turn Guadalcanal into an American bastion. Henderson Field became a base for bombers and transports. Two additional fields were opened to host the fighters: USMC airmen and their F4Fs went to Fighter 1, while Fighter 2 supported a mix of USMC and AAF units, including the P-38s of the 339th Fighter Squadron, commanded by then-Captain John Mitchell. On January 5, he scored his fourth aerial victory—his first while flying a P-38; before the end of the month he had scored twice more to become the newly established 13th Air Force’s first ace.

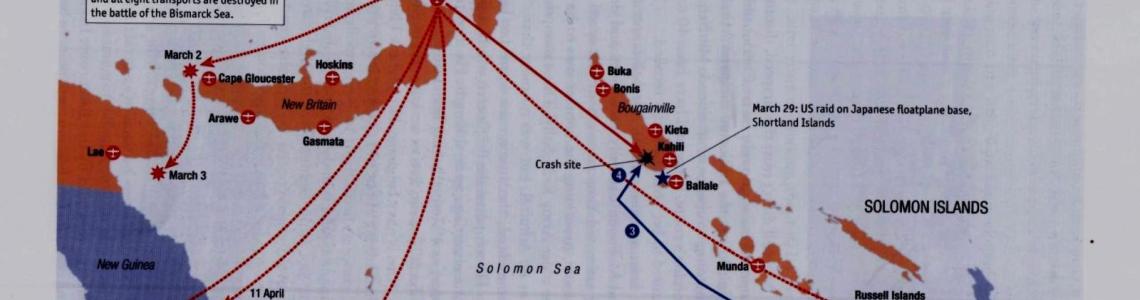

The Japanese recognized that they must retake the initiative, and quickly, if they were to counteract the Allies’ growing strength in men and materiel in the Solomons. Given the stakes involved, Admiral Yamamoto saw it necessary to take personal charge, and in early April he and his staff moved south from his secure base at Truk in the Caroline Islands to Rabaul, about 660 miles north of Guadalcanal. The response that his staff devised, called Operation I-Go, was complicated, under resourced and hampered by distance and difficult climactic conditions. Unsurprisingly, the results were less than spectacular. In an effort to encourage his airmen, Yamamoto decided to conduct a personal inspection of the frontline bases just south of Bougainville on April 18. His administrative assistant dispatched an encrypted message detailing the Admiral’s itinerary down to the minute. What he could not know was that, in addition to its addressees, the message was read by US Navy codebreakers.

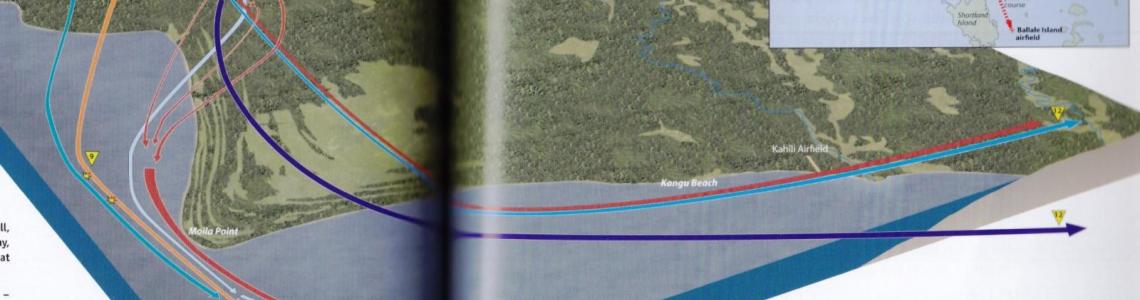

Sheppard does an excellent job of describing the actions that followed. Although the Navy was in charge, it was clear to all concerned that the AAF’s P-38s were the only fighters on Guadalcanal with sufficient range to intercept the Admiral’s airplane – and even then only if larger external fuel tanks could be borrowed in time from 5th Air Force. They were. Major Mitchell was given carte blanche to plan the route and to choose the shooters and their escorts. He acted. The team largely depended upon dead reckoning to be at a precise point in time and space over 400 miles from Fighter 2. They arrived. Their chance for victory required that Admiral Yamamoto’s schedule should be strictly followed. It was. Their success demanded superb piloting skills and good marksmanship. They performed.

To my mind, where Sheppard’s text is most rewarding is the objectivity displayed in his analysis of the mission and its aftermath. The claim for credit regarding the shoot-down became a very controversial topic in the postwar years. Sheppard doesn’t say outright who deserves credit and who doesn’t, although he clearly states who is the most credible claimant. He recounts three of the shooters’ descriptions, notes their divergences and then points out a critical fact: none of them were formally debriefed after the mission. In fact, they subsequently made claims for three Betty bombers and three Zero fighters, and it was only in the 1990s that we learned from a surviving Japanese escort pilot that there were only two bombers shot down that day. None of the escorts were even hit, let alone lost. But, in fairness, things seen in the heat of battle might be real. Or not. And if you weren’t there…

So, this book is being reviewed for a scale modelling organization, and that brings up an important point. How useful is this book to a modeler? There are two answers to that. If you’ve opened a kit box and you’re in need of guidance, then look elsewhere. There are no drawings or color profiles here. The photos are very good, but very small. Instead, I would say that this book offers great value as a motivational tool. Why, after all, do we build scale models of military aircraft? Yes, an airplane can approach the beauty of a sculpture in its shape and form. But an airplane is a machine, and machines are created and used by humans. When we build, do we not honor the courage and skill of the humans who flew these machines, even perhaps without regard to the cause for which they flew?

Thanks to Osprey Publishing for providing a review copy of the book.

Comments

Add new comment

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Similar Reviews