Alfa Romeo 2300 8C Monza Race Car

The Kit

Italeri’s new multi-media Alfa Romeo 2300 8C “Monza” race car kit comes in an impressive box measuring 22” x 11” x 4-1/2” (Photo 1). An illustration of the box contents is shown on one of the box lid flaps (Photo 2). Upon opening the box, you find a 28-page instruction booklet, four plastic bags containing 10 styrene sprues, including duplicates of the “D” and “G” sprues, two bags of hardware with various sized screws and nuts, a decal sheet, masking sheet, steel photoetch sheet, nylon mesh sheet, rubber tires, copper wire, rope and rubber tubing (Photo 3). The kit offers using either masks or decals for the No. 28 race car driven by the famous Italian driver Tazio Nuvolari, a nice feature. To try both for the purpose of this build review, I masked the radiator No. 28 and used decals for the body numbers. I used the length of rope to replicate its use as heat protection on the exhaust pipe in the Nuvolari car. The nylon mesh, along with a piece of photoetch, can be used to replace the one-piece plastic screen for what appears to be the supercharger air inlet. Parts for the street version of this car are not included, so the builder can assemble either the No. 28 car or a generic race car with a few of the additional parts provided for the front grill and exhaust pipe insulation. I opted to build the No. 28 version.

General Comments

There is no question this kit gives the modeler a chance to build an iconic race car, a Bugatti beater if you will, as it was in 1931-32. It results in a beautiful model with a great looking engine. Parts fit overall was excellent with only a few tricky assembly issues. The decals were excellent, very quick releasing and, in the case of the body’s split numbers, perfectly cut. Wire wheels, which can be a problem on some kits, went together easily and look fine. The supplied tires are also very nice. I am quite pleased with the results. The main challenges I encountered in the build had to do with the instructions and the color callouts or, more specifically, the lack of color callouts.

In anticipation of receiving the kit, I did some preliminary research. The cars in the references I found did not appear to have a consistent red body color and, while you can’t trust photos for color accuracy, most were in a color range that varied from a basic red to maroon. Had I not found the color specified on the box, Tamiya TS-39 Mica Red, I was ready to use Humbrol Crimson, which to my eyes has a more vintage look and is more in the range of the colors in the photographic record. But again, sticking with the build review, I went with the Mica Red color called out on the box, which happens to be a fine-flake metallic paint. I questioned the existence of metallics back in the day but found they were introduced in the late 1920’s, so I didn’t feel badly about using one on this model.

What I found somewhat confusing were the colors listed in the instructions vs. the box lid. On Page 4, six colors are called out, coded A through F, none of which is Mica Red. The B coded color is labeled Gloss Red, F.S. 11302, and provides an Italeri paint number. However, I opted to make all major red parts of the car, especially the body cowls, Mica Red in accordance with the box listing. Also, Flat Black and Metal Gloss Silver are listed on the box, but Gloss Black and Flat Aluminum are listed in the instructions. Only the A through F coded colors are called out in various parts of the instructions and many parts do not have colors indicated at all. I would prefer to have all the parts color coded. I therefore relied upon experience and reference photos of real cars to decide what to paint each part. Note I did not use an airbrush on this model. All parts were painted from spray cans or hand brushed.

One excellent reference for this car is a Jay Leno’s Garage episode, accessible on YouTube or Leno’s archives. Jay owns a replica 1932 2300 8C outfitted for the street produced by Pur Sang, an Argentine company that builds them using parts made exactly like the original. You, too, can have one for between $400k and $500k, a small fraction of the eight figures a real 2300 8C would set you back. The episode amounts to a walk-around of the car with particular attention paid to the engine compartment. Therein you see, for instance, the interior of the hood being unpainted aluminum, which I followed on this model. Parts like the firewall were a darker metal and I used flat gun metal (instructions code D paint color) for that as well as for the suspension shock assemblies as called for in the instructions. As enjoyable as all of Jay Leno’s Garage shows are, this one is a must for anyone wanting a close up of this Alfa, and who wants to hear its fine exhaust note as it motors down a California freeway.

The other challenge concerns the instructions themselves. Some good features of the instructions include the diagrams and measurements of the screws, necessary to differentiate their small sizes. The ignition wiring and points of attachment to the distributor are nicely diagrammed and easily read in Step 17, and the warning not to cut the pins off of Parts 1I and 2I on Page 2 is appreciated. However, the numbered parts have a letter suffix indicating their sprues and there were three parts with incorrect letter suffixes. In Step 13, Part 16C is mislabeled 16B. In Step 28, Parts 23C and 26C are mislabeled 23D and 26D. Also, the wiring and cabling (Lines B, C, D, E, and F) are shown at the engine components by dashed lines in Steps 14 through 18. I did not realize that the dashed line meant that they were not to be attached to the engine at this point of the build, i.e., the dashed lines identified the locations of attachment but indicate not to attach at those locations until later (Step 26). As depicted in Step 26, these wires are to be attached to the back of their corresponding instrument gauges and inserted through the firewall, then attached to the engine components after the firewall and instrument panel are glued into the main cowl. So, I had to detach the already installed wires from the engine, attach them to the back of the instruments, and reattach them to the engine components after installing the instrument panel and firewall. Luckily, I tagged each wire with their letter codes before having to do the above reinstall procedure, so I knew which went where. The meaning of the solid and dashed routing lines should be defined in advance in the instructions.

Finally, it would be a better experience for modelers who are not bolt-headed car builders if the kit parts were named in the instructions as opposed to just numbered, so you know what it is you’re putting together. I learned a lot about Formula 1 cars from building detailed kits that contained a complete nomenclature of their component parts. Vintage cars like this Alfa have things unknown today like manual spark retarders, and I still don’t know what the levered component is on the floor beside the driver’s seat to which I attached rubber tubing.

The Build

This kit has more mold release pins and pin marks than any kit I’ve ever built (Photo 4). Even small pieces have them. It would be good to have them identified in the instruction illustrations to avoid cutting off pieces of the parts themselves, which I’ll admit I’ve done more than once. I sanded off pin marks prior to assembly of all parts in Steps 1 and 2, assured a good bond with screw attachment reinforcements Parts 37A and 38A, and pre-painted the whole assembly after fitting the front axle. The fit of the frame parts was excellent (Photo 5).

The suspension components come next. I needed to remove mold lines and mold release pins from all the leaf springs. I opted to paint the leaf springs gloss black vs. red, one of the two optional colors called out in the instructions. The friction plate shocks include a sandwich of 10 disc plates each with two shocks attached at both ends of the front and rear axles. These are somewhat intricate. Be sure you assemble the parts in the right order and assemble them with the screw attachment points angled as shown (Photo 6). Those parts with pin marks can be oriented so the marks are hidden. I brush-painted these after assembly with Testors Flat Gunmetal Non-buffing Metalizer. Attaching the shocks to the frame assembly required a deft touch (Photo 7), as did most of the screw attachments in this kit. The screws in this kit are very small with thin slots in the screw heads. I needed to find a tiny, fine flat-bladed screwdriver to install them. While a plastic nut wrench is included in the kit on Sprue A, a suitable screwdriver in the kit would be welcomed. Also assure that the self-tapping #14 screws are perpendicular to the frame when screwing them in. They are easily driven in at an angle if care is not taken. Note that I needed to ream out the screw holes to get the screws all the way in. Widening holes was necessary for almost all the attachments made in assembling this kit. Pre-fitting of all parts in this build is crucial.

The rear end and suspension as per Steps 6 and 7 went together well (Photo 8) as did the rear attachment to the main frame. This resulted in a very strong assembly (Photo 9).

Installing the front steering linkage (Step 9) is tricky. A small amount of CA to hold the nuts in Parts 35A is helpful in getting the screwed parts into place (Photo 10). Attach Parts 16I and 17I, and Parts 16A and 17A to Parts 35A, and assure they are properly aligned before gluing on the wheel disk. Be careful with Parts 16I and 17I when removing burrs and plating as they are frail. Note that the front wheels are angled in at the ground (Photo 11).

The engine assembly was next. As previously mentioned, color coding of the engine parts is not completely called out in the instructions. Reference photos indicate shades of aluminum on the real engine. I chose to use Testors spray Aluminum Plate Buffing Metalizer for the bulk of the engine parts, Testors Gunmetal on the sections called out for color code D, and Titanium Buffing Metalizer for the upper section of the engine, Part 3B, to which the spark plugs are installed. This gave the completed engine a realistic variation of metallic shades.

I often use Pactra Trim Tape cut into thin strips to represent hose clamps on radiator hoses and used it on the hoses on this model (Photo 12). Note that the black plastic tubing included in the kit had a flat cross section. I used some leftover thin tubing from other kits in a couple places and fed some telephone wire inside sections of the kit-supplied tubing to give it a more rounded look.

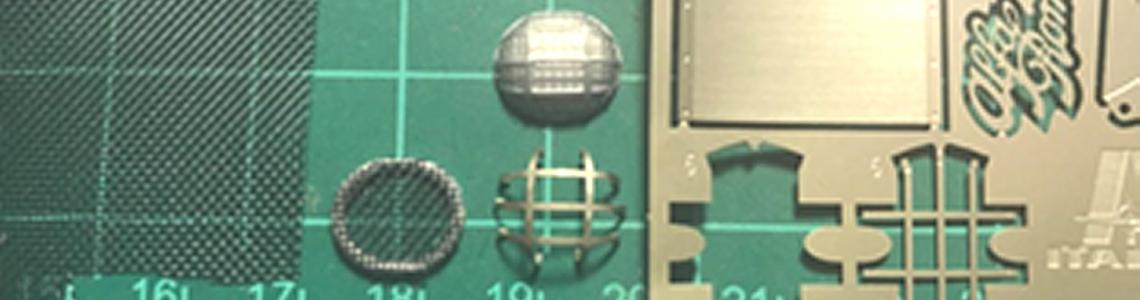

The kit provides two options for what I am guessing is the intake screen of the supercharger: a single plastic piece representing the frame and screen, Part 32B; and a photoetch frame with a mesh screen underneath that you cut out to shape from the nylon sheet provided. I chose the latter option after checking reference photos. The photoetch frame looks much more realistic than the plastic option. I did use the plastic piece to start the bend in the photoetch frame and finished the bend with small needle nose pliers, carefully bending in the tips that form the gluing surfaces of the frame. The photoetch in this kit is steel not brass and is stiffer than typical brass PE. Two of the frames are provided in case you spoil the first one while trying to shape it (Photo 13).

The finished engine assembly (Photo 14) glues to the front frame cradle piece, the rear drive shaft tunnel, and right and left frame channels using four screws on each side. The specified #14 screws did not reach in far enough without my countersinking the holes to get the screws to bite (Photos 15 and 16).

I painted the radiator semi-gloss black and used the kit-supplied mask to spray a flat white number 28 on the front before installing it in Step 19. Better to paint the number at this point than after it is installed as indicated in Step 28.

When installing the steering link, Part 18A in Step 20, I needed to remove and realign the angle of the front wheels. Instructions call for securing the link using the old-fashioned hot screwdriver method. Haven’t done that for a few decades, but it works.

The front axle needs to be in the proper position for the under-chassis linkages to fit (Steps 20 & 21). I needed to tweak the axle position about a millimeter to the rear so that Parts 5A and 8A reach their attachment points. Again, holes needed to be enlarged and pre-fitting is important.

The seat color is called out as either gloss black or flat medium brown, F.S. 30111. I opted for the latter based on personal preference and a reference photo. I primed the seat with Tamiya fine white primer and used Tamiya TS-1 Red Brown spray lacquer, which is a match for the F.S. color spec. The seat and floor assembly snapped nicely into place. Care is required to get the three pedal shafts on Parts 41B and 42B through the floorboard when installing that assembly.

Instructions call for tubing I to be attached to Part 20A on the floorboard to the right of the driver’s seat. I cut the tubing to the 130mm length specified but it was too short to reach 20A. I added a styrene rod drilled out at the ends to make the connection (Photo 17).

The rear cowl fit perfectly on the frame behind the seat (Photo 18). The two tubing runs that attach to the fittings on the right side of the rear cowl could not be stretched over the pins without pushing the fittings off the cowl. I bored out a 1.5mm rod with a #62 drill bit to make small collars to allow the ends of the tubing to easily fit over the tips of the cowl fittings (Photo 19).

Locating the ends of the two 60mm tubes that drop down from the fittings atop the rear cowl are not specified in Step 24. Box photos show them fit through the flange separation near the joint between the main and rear cowls, which is where I fed them (Photo 20).

Instructions in Step 26 show instrument decals put on after instrument wiring is attached behind the panel. I recommend decaling the gauges and installing the clear gauge faces ahead of the wiring (Photo 21). The fitting and gluing of the firewall and instrument panel is not easy. Care is needed to get the tubing through the firewall and get the instrument panel to the correct position without pulling the tubing off of the back of the gauges prior to gluing. Completed firewall and wiring is shown in Photo 22.

The Nuvolari race car had a rope wrapped around the exhaust to protect the rider from the hot pipe. I attached the rope with a very small amount of CA at the front end, then wrapped the rope tightly and put a small amount of CA every three or four windings. The result turned out just right (Photo 23).

The underside of the hood on the replica car was unpainted aluminum. After filling all the pin marks with a CA/talc mix (my favorite filler) and sanding them smooth, I painted the undersides with Tamiya AS-12 Bare Metal Silver. The latter may be an aircraft color, but it looks just right in this application and it can be masked without damage, which I needed to do to avoid the exterior Mica Red from spraying through the hood vent slots.

Step 29 of the instructions show two copper wire ties wrapped around and holding the ignition wires to the center support brace (Parts 13A/14A) that runs from the firewall to the radiator. There is no way I could tie the copper wire around that support the way it is shown in the instructions without pulling off the brace or one or more ignition wires from the distributor. I tried and I did. So, I made a winding out of two small lengths of the wire, spiraled them around the brace and ignition wires and tightened them as gently as possible (Photos 24 and 25).

I recommend completing Step 32, the underside gas tank and tubing connections, before installing the hood pieces in Step 31. The hood and nose cowl/radiator assemblies detached when I was installing the gas tank with the car inverted on a jig. If I had done the gas tank first, I would have avoided the mishap.

The nose cowl fits tightly to the radiator and has little surface to glue it to the frame. Part 13E is essential to positioning and securing the nose cowl in place. It also provides the correct spacing for the upper hood pieces to fit. Applying glue to 13E must be done carefully to avoid marring the external paint surfaces of the model. I used a lot of GS Hypo cement in constructing this model because it is clear, does not mar paint surfaces, allows repositioning pieces before it sets, and can be removed with alcohol. Most of the external pieces, e.g., the hood clips, nose cowl, windscreen and rear cowl fittings were attached with this cement.

The final steps of the construction, including the steering wheel and column (painted the same color as the seat), wheels, and the windshield, went smoothly. The modeler then has the choice of closing the hood or opening either side for display. No modeler in his or her right mind would display this model with the hood closed. The engine begs to be seen. I opted to display the model with the right side hood open (Photo 26).

In summary, I can attest that with careful planning, and by identifying the few insufficiencies in the instructions in advance, this is one satisfying build that results in a great looking model.

Thanks to Italeri, MRC and IPMS USA for the opportunity to do this review.

Comments

Awaiting my kit

Thanks for all the hints!

Following the Instructions

I have found the instructions to be a bit vague at times but your notes on your build have been invaluable. Common sense makes a great building companion as well. It is a pity that your photos have been cropped by the site as they are very helpful. I am enjoying my build and today will finish the engine, ready to install tomorrow.

Add new comment

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Similar Reviews